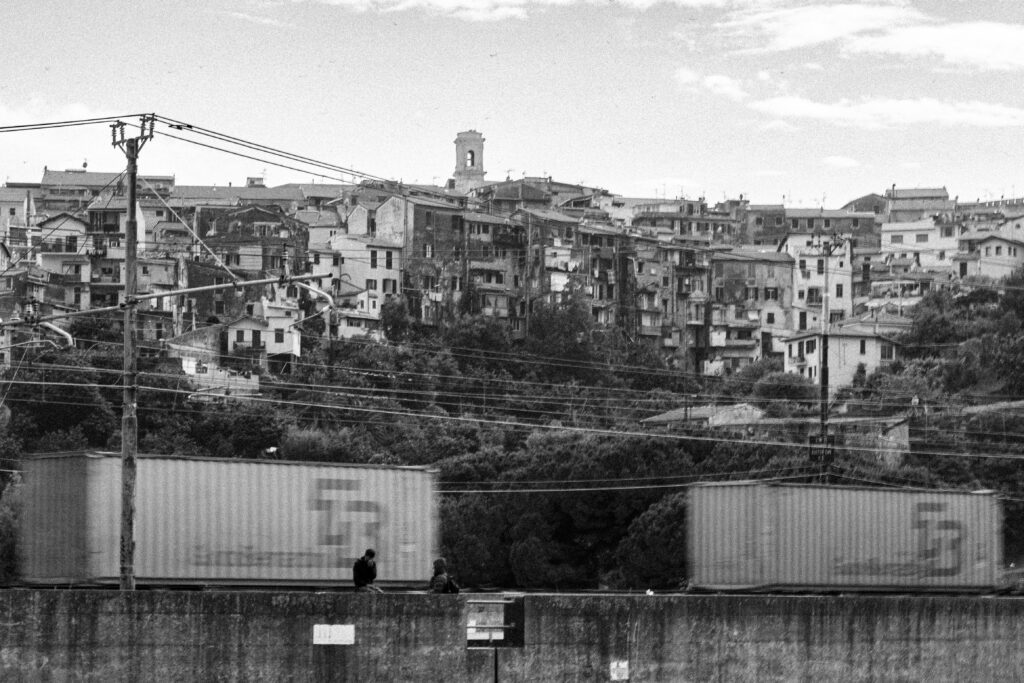

Ventimiglia. France – Italy border

THE ITALIAN BRIDGE

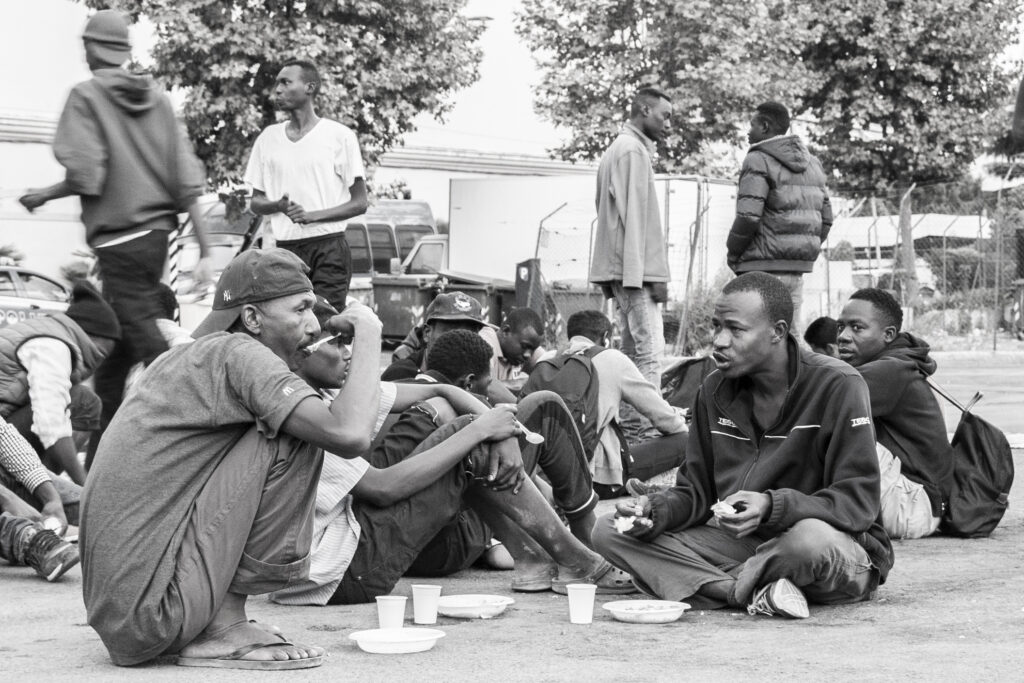

For some refugees Italy represents just a bridge, a country to cross in order to reach the final destination of their migratory path in northern Europe. Others instead, decide to leave Italy only at a later stage, pushed by despair for the impossibility to see a concrete prospect of integration in the country because of the inadequate reception conditions, the difficulties in obtaining documents and legal family reunification, the difficult access to the job market.

Throughout their journey along the peninsula, from when they enter the country till they reach the alps, refugees who try to move up have to face direct or indirect violence: episodes of arbitrary deprivation of personal freedom, physical and psycho- logical violence and inhuman treatments have been reported both following disembarkation as well as during internal borders’ control operations.

Identification procedures. Since 2015, Italy, in order to ensure prompt registration and identification of incoming migrants according to the European Agenda on Migration, implemented the s.c Hotspot approach through the provision of a mechanism of pre-identification and registration to be conducted directly at disembarkment points and inside Hotspots, closed identification centres organized to provide first aid and divide asylum seekers from “irregular economic migrants”. In few years Italy has reached the goal of 100% identification of migrants rescued at sea, but what is the human price of such efficiency?

Most of the migrants interviewed in the last three years complained that at the time of registration and identification they were not aware of their obligation to seek interna- tional protection in the first country of arrival, of the possibility to refuse fingerprinting and of the consequence of such refusal. Many of those who refused to be fingerprinted reported that they were forcibly identified through violence or intimidation.

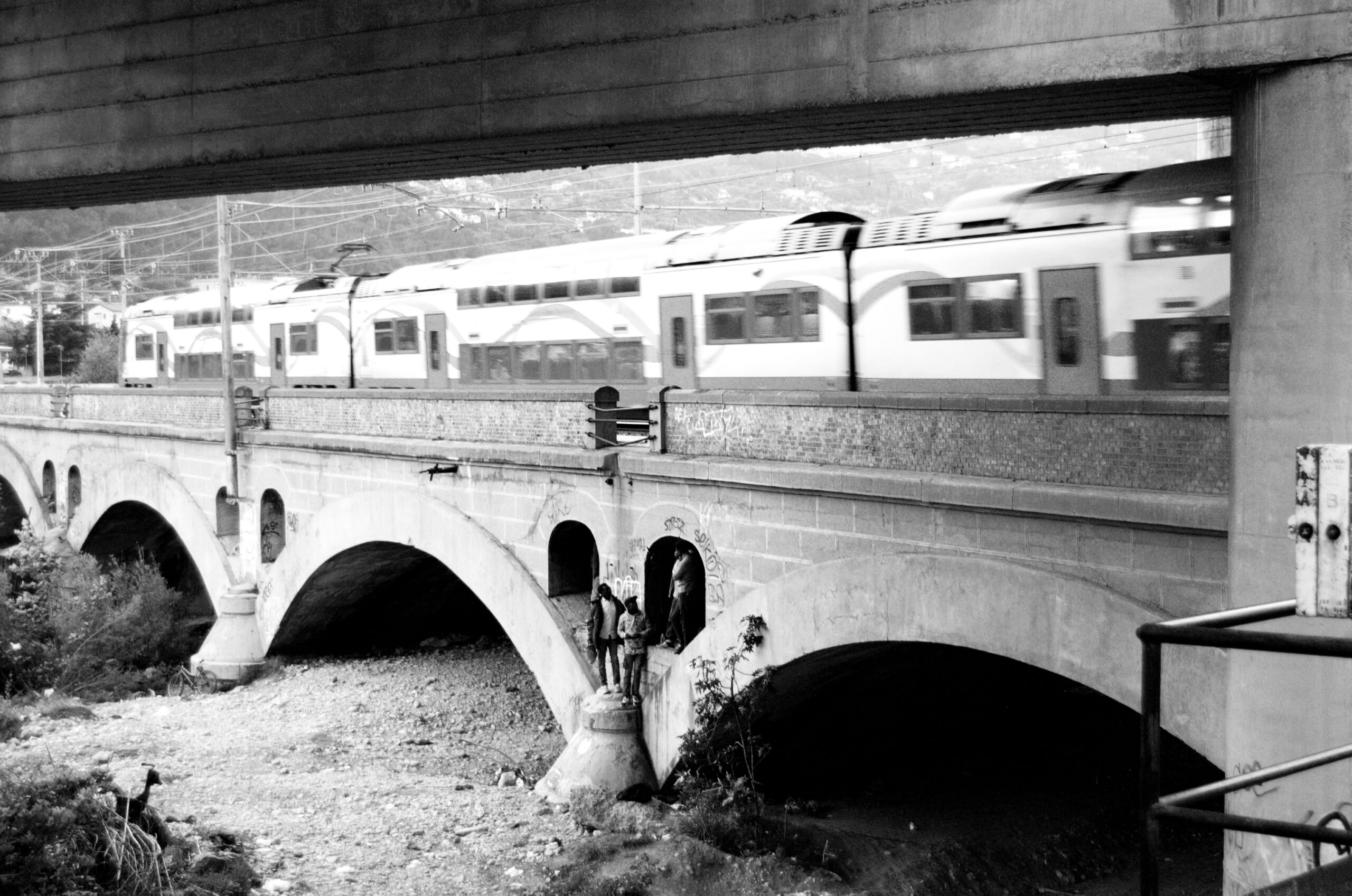

It is June 2016 when A., a 18-year-old boy from Darfur, under the hot sun that hits the parking lot in front of the church of Sant’Antonio in Ventimiglia, tells us “I arrived in Calabria and I was taken to the First reception centre of Isola di Capo Rizzuto to be identified. I opposed to identification and I was confined with other six boys in a container. It was all dark, there was no window and no bathroom. It was re- ally hot, I thought I was dying. They left us there with no food and just few bottles of water for three days. Every day two policemen stepped in. They told us: . On the fourth day they took me for identification again. I tried to resist but they beat me with an electric beat on my legs, hurt my back and pressed with force my hands on the machine. they asked: and I said <No, I want to go in England>. Afterwards, they gave me some papers (an expulsion decree written in Italian) and they took me on a bus with both hands and ankles tied. The journey was long and we couldn’t eat. I was taken to the Centre for Identification and Expulsion of Caltanissetta (Sicily). After few days I was released and I run away to reach Ventimiglia. Italy is so bad, I want to go to the UK.”

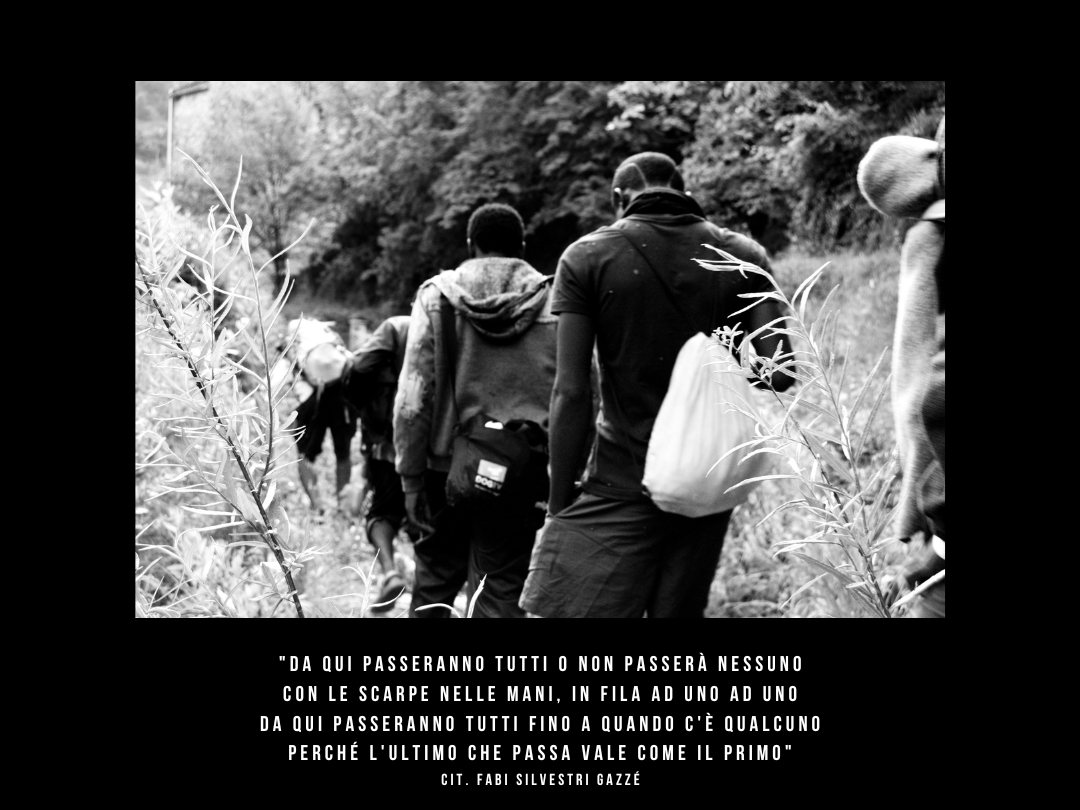

Violation of human rights at the internal borders. Episodes of violence have been reported also by migrants who tried to cross the northern internal borders in the at- tempt to reach Switzerland, from Como-Chiasso and France, from Ventimiglia-Men- ton.

In Como, in the spring of 2017, M., 18-years-old, still deeply shocked, said “I reached Como and tried cross on train to reach Switzerland. The Swiss border guards stopped me in Chiasso station. They lead me in a close room where I was forced to stand all naked and subjected to physical inspection. I felt so humiliated. Then they drove me to the Italian police office in Como with other migrants had just been subjected to the same treatment. One policeman found that I had Italian documents and said to his colleague and I replied . So, the other policeman took me from my back, told me <oh, do you like to joke?> and started to kick me and hurt my face until I fell down. Then the first policeman took my neck from the back, forcing me to stand and hurt my head badly on the wall. I lost consciousness”.

The border of Ventimiglia-Menton has always been the main crossing point and since 2015 became the laboratory where the French and Italian governments could develop their repressive policies of border management, policies characterized on both sides by the systematic violation of migrants’ fundamental rights. On the French side, migrants are deprived of personal freedom and pushed back every day without any assessment of their vulnerability and without the possibility to apply for protection, even if they are unaccompanied minors. Lately, the French Controleur General des lieux de privation de liberté [42] and the French Commission National Consultative des Droits des Hommes issued two important decisions that confirm the denounces of NGOs and civil society.

“We tried to cross the border on foot. We were on the path when French soldiers stopped us. They pushed us down, we fell on the ground and they kicked us badly. Then we were taken to the police office at the border. We were kept in a closed room with no water and no foot for one day, with a really high freezing air conditioned. Only one day after they released us forcing us to take the train to Italy”, told us in September 2017, N. e O. 17-years-old.

Smuggling, sex and money. The suspension of Schengen agreement by France since 2015 has encouraged the development of a well-organized network of traffickers and forced, once again, migrants to endanger their lives to cross the border along impervi- ous unmarked mountain paths, hiding in trains or walking the tunnels of the highway that runs above the coast.

The human cost of the trip often does not end in the danger that they are forced to face, but also in what they are forced to suffer to pay back the traffickers. The cost of the passage for France varies depending on the comfort of the trip and duration of the passage: for 100-150 € migrants are crammed into overhead vans or cars, closed in the trunk, in the trucks or closed by the traffickers inside the doors of the train that contain the electric cables.

To the children alone and to the women who can not pay in euros their passage, the package offered by traffickers provides the opportunity to pay back the offer with sexual favours.

B. a 15-years-old Eritrean girl who was traveling alone with her 6-years-old brother and another Eritrean lady, said “A Nigerian smugglers asked us for sex twice in change of a passage. We refused but he asked to other girls who were in the train station”.

Bad government assistance to the migrants. In addition to the dangers related to illegal border-crossing migrants, waiting in the limbo of the city had to face for long time inhumane reception conditions in which: in the last years 5 migrants died drowned in the river or near the beach while they were trying to wash themselves, due to the absence of public baths and water sources. Other two migrants died hit by cars as they walked the stretch of high-distance road that divides the city from the govern- ment centre Camp Roya, which stands in an isolated area.

The game of the goose. On the Italian side, with the intention to “decompress the migration pressure on the border”, since 2016 the Italian Ministry of Intern put in place a new strategy to forcibly remove from the town of Ventimiglia the migrants pushed back from France. Forced deportation of migrants to the Hotspot of Taranto or to other closed identification centres in southern Italy are organized weekly by the Italian police. Since all the migrants have already been identified upon arrival in the emergency governmental Camp Parco Roya or at the border after being pushed back from France, the only objective of such measures is to arbitrary deprive migrants of their personal freedom. “After being released from the gendarmerie, I was taken to the Italian border-guards office. They took again my fingerprint, and gave me a paper with my name and a number. There was no interpreter. I was then taken to a room with other guys and we waited for some hours until they forced us to get on a bus. The journey took 17 hours. The bus was followed by another one full of policemen, and other two cars of the army. We stopped 3 times, but we could get off only one time. We had to go to toilet in open air when the bus stop in the middle of nowhere on the highway. We were 22 and there were 18 cops surveilling us.” said H., 23- years-old, from Sudan.